Professor Lutz Jäncke is a neuropsychologist and cognitive neuroscientist who has spent decades studying the plasticity of the most powerful but mysterious organ of the human body: the brain. He is co-founder of The International Normal Aging and Plasticity Imaging Center at the University of Zürich, from where he explained why learning and creating by hand is so important for our increasingly distracted brains.

The Tools to Hand

Writing Culture

Professor Jäncke, you have been working in the field of neuroscience for over 30 years. What first sparked your interest in the brain?

I became fascinated by the human brain when I saw a post-mortem brain for the first time, during an autopsy in 1980. The motivation to explore this tiny little organ more deeply was planted there and then. The brain weighs 1.2-1.4 kg; it’s such a small thing but it is responsible for everything we do: what we feel, what we think, how we move. At that time I was in the US playing water polo in a university team and was required by my coaches to enrol in some courses, one of which was about neuroscience. I went and was very fortunate to hear the lecture of Roger Sperry, a very famous neuropsychologist who received the Nobel Prize just one year later. Through these experiences, I realised this was the path for me.

How “plastic” does the brain remain throughout our lives? How do tools we use, such as pen and paper, or, more recently, keyboards and touchscreens, affect this?

So far, no one has examined this question in great detail. But on the basis of what we have already learnt, everything that you do intensively and frequently has some kind of influence. For example, if you play the piano for a long time that will shape those areas involved in controlling piano playing. The same will happen to an artist painting throughout their entire life. With it comes to performing touch screen manoeuvres every day, it’s a different kind of motor behaviour but I’m pretty certain that will also shape your brain. Taking this further, you can say that everything that you do frequently – everything – is going to shape your brain. And it’s also everything that you don’t do. I like to combine both these ideas in one phrase: “use it or lose it!”

Vera Hartmann / 13 Photo

Research has suggested that if you write something down by hand rather than typing on an electronic device, you are much more likely to remember it. How much is this to do with the “slowness” of writing?

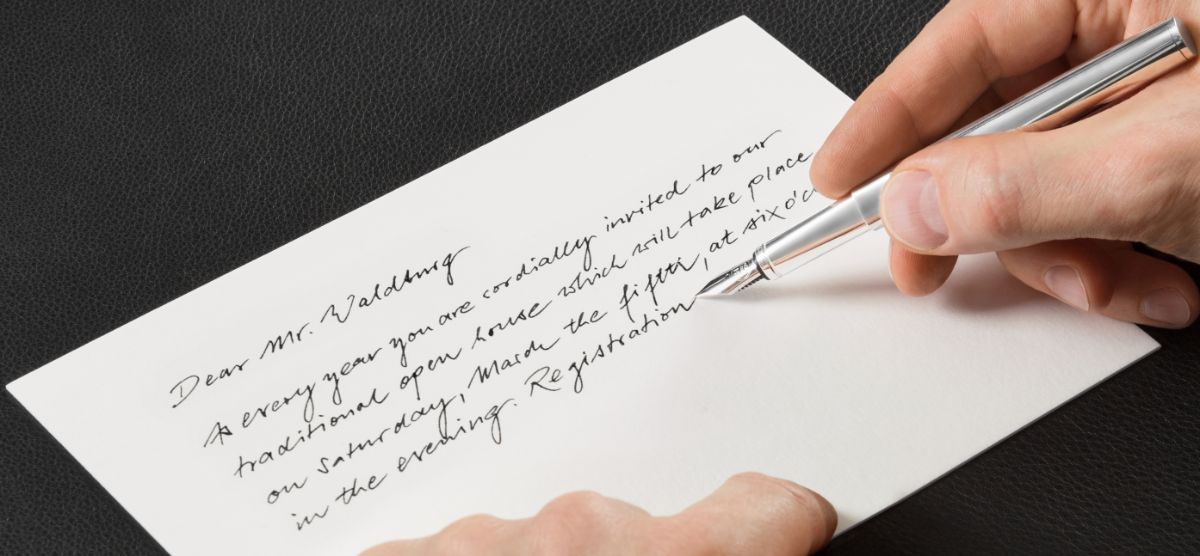

Indeed, there have been a few studies that have shown that what you write with your hand finds a more efficient way into your long-term memory. The interpretation is relatively easy: when you write, it takes time to put the words on the paper. The process also involves a kind of multimodal perception – first, you see the colour of the ink as it is absorbed into the paper; second, you see the shapes of the letters developing as your write; thirdly, you hear the scratchiness of the nib; and fourth, you feel the movement of your hand and arm. That’s just four elements but there are many more. All of them are linked to what you have written down, correlated with the words. Our brain likes this a lot, because long-term memory is what we call a kind of semantic, network memory: it connects. The information we remember very well from long-term memory is that which is connected to many other pieces of information. If you are going increase your memory performance, when you learn something you have to connect those different elements whilst you learn. When you write something down, you do that automatically.

Underlying all this is a truly neuroscientific issue: the fact that you have to do it with one hand. That’s very important. The use of a single hand has a tremendous influence on the way the brain is activated. For example, if I write with my dominant, in my case, right hand, the motor areas controlling that are located in the brain’s left hemisphere. The motor areas controlling my left hand are on the right. But when I write with my right hand, the motor areas on the left of the brain are activated, which are located adjacently to the left-sided language areas. The flow of information between them is very fast and efficient. If I were to write with my non-dominant left hand, my right-sided motor cortex would be activated to synchronise with the left-sided language areas.

But the information would have to cross what is the called the corpus callosum, taking much longer to get to the other side. Writing with one hand, your dominant hand, whether right or left, makes sure that the motor control is tightly and efficiently linked with the language areas. But when you write with both hands, as you do on a computer keyboard… well, you can anticipate the problem. There is a constant switch of information between right and left hemisphere. It’s more efficient to write with one hand – with a pen – because it’s easier for motor control to get that connection with the language areas.

Virtual reality hardware is becoming more and more sophisticated and able to incorporate multi-sensory elements – sight, sound, touch – into the experience. Does that mean it could catch up with and even replace the act of slowly learning something by hand?

It’s a good question. I personally believe that developing ideas in a creative way using a computer is not easy – even for someone really skilled. When I am writing, I tend to put my ideas down on paper first, writing by hand. When I do get to a computer, I don’t use complex software such as Microsoft Word, until perhaps right at the end. Instead, I use the most simple text editor I have, which is almost like a typewriter. That frees me from the distractions that come with more complex programmes. When you have to be creative and really think about things, it is necessary to keep your focus of attention on the main task. Our contemporary situation is very problematic. We are so distracted, by all kinds of things: complicated software, email notifications, news alerts – this is very bad for us because we are not, in fact, natural multitaskers. Actually, we have evolved not to multitask. We can only be efficient at complicated cognition tasks if we focus on the task for quite some time – 30 or 40 minutes or so. That’s the way we have to work. So we have to learn, to relearn actually, to focus. I anticipate that in the future, more people will go back to our earlier roots when they work. The basic cultural abilities of writing, reading, music-playing, painting, talking, discussing will become even more important the more diverse and complicated computers and technology become.

Professor Lutz Jäncke is the head of the chair of Neuropsychology at the University of Zürich and a passionate collector of fountain pens.